May 22, 2017 / Esther Choy

A good presentation is not about how well we speak. It’s about how well we connect. We think about these connections constantly at Leadership Story Lab, so I’ve developed a set of best practices for engaging your audience. Here are 35 key tips based on information I’ve been gathering since I founded Leadership Story Lab in 2010.

I know… it’s a lot to process. Because of that, I’ve organized the advice into four chapters:

- Chapter One: Understanding your audience

- Chapter Two: Crafting engaging stories

- Chapter Three: Gaining and retaining attention

- Chapter Four: Beyond presentations, beyond your comfort zone

Chapter One: Understanding Your Audience

A supervisor or colleague asks you to speak at an upcoming event. What’s your first thought? Is it, what will I say? or is it, who will I be talking with?

Understanding your audience, what they care about, and what they need to hear is the most important consideration when preparing for any presentation. Considering who is in the room gives your message the best chance of connecting with your listeners. Not only that, it can make presentations less stressful because you go into them with a clearer picture of who you’re talking with.

1. Target your real audience.

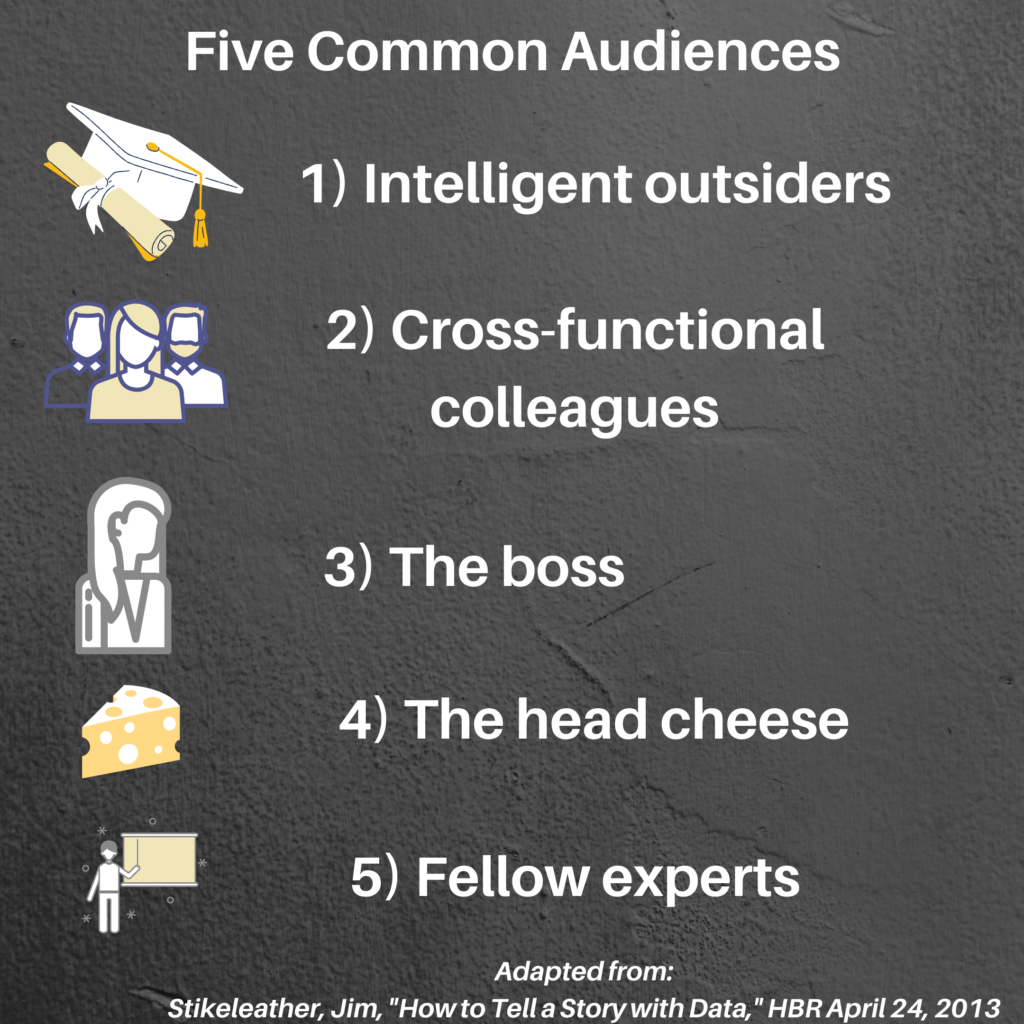

There are five categories of audiences, according to Jim Stikeleather in the Harvard Business Review. One of the best practices for engaging your audience is to take time beforehand to discern which one of the five is your target audience.

Each type of audience will want a different level of detail. That means you’ll need to create a completely different kind of presentation depending on which audience category you want to reach.

The Five Categories:

1) Intelligent outsiders:

Even though this group does not share your area of expertise, they are nonetheless highly educated in other areas. A “dumbed down” presentation may frustrate or even offend them. So don’t water the content down, but do explain sections that might be unclear to those outside your field. Don’t skip nuances, but do cut every unnecessary detail.

2) High-level cross-functional colleagues:

This group is composed of your colleagues from marketing, operations, finance, accounting, sales, human resources, and other departments. They’re familiar with your topic but want to refine their understanding. Ultimately, they want to know what your topic means for their department. Spell that out for them.

3) The Boss:

Your direct manager has to understand and stand by your work. Your work and her understanding of it can both affect her career. As Jim Stikeleather says in Harvard Business Review, the boss wants to understand “intricacies and interrelationships with access to detail,” and she wants her understanding to be “actionable.”

4) The Head Cheese(s):

These are your manager’s managers, the busiest executives. Think: why should they care? Think: what should they do about it?

5) Fellow Experts:

These audience members know just as much about your topic as you do, if not more. Give them the level of detail they crave. After all, they will most likely want to explore your methodologies and results– or even critique them.

2. Write down what you know about your audience.

Once you’ve identified your target audience, take out a piece of paper and divide it into two columns.

Once you’ve identified your target audience, take out a piece of paper and divide it into two columns.

Column 1: write everything you know about your audience.

Who are they? What do they love and loathe? What are their most pressing challenges?

Column 2: write everything you don’t know. This helps you avoid assumptions about your audience.

My book, Let The Story Do The Work, includes more detail to help you analyze your audience, but I’ve found this simple exercise to be an effective way to get started.

3. Understand their moral framework.

If we want to persuade others, we’ve got to see the world from their vantage point. And to do that well, we first have to know the viewpoints our audience has expressed, and then dig deeper to understand the moral or ethical framework underlying those viewpoints.

People’s political stance flows from their ethical framework, as a recent study from Matthew Feinberg of the University of Toronto and Robb Willer of Stanford found. The views that conservatives hold on, say, immigration, might flow from their values of loyalty or patriotism. For liberals, their views on this issue might flow from ideas about reciprocity between countries, or caring.

Most people voice opinions on heated topics without even realizing that loyalty or caring has led them to the opinion they hold. What appears to be a disagreement about political ideas is actually a fundamental disagreement over which ethical systems should govern politics.

4. Make an offer.

When we hope others will change their minds, one of the best practices for engaging your audience is to make an offer rather than blaming.

After Trump’s executive order banning immigrants from seven countries in January 2017, someone tweeted that “history will judge us very harshly.” How could that be reframed as an offer, which may ultimately be more persuasive?

Here’s how one author reframes it:

These refugees and immigrants are just like our family members who came to America in years past to seek a better life…. That dream is what our nation was founded on, it is what brought our grandparents and great-grandparents to this great land, and it is the great success story that these immigrants want to be a part of.

This would be a starting point of making an offer instead of blaming.

This phrasing invites the person to reimagine the situation. And notice all the patriotic language: the phrase “this great land,” and the references to success stories and the American dream. This speaks to conservative values of patriotism and loyalty.

However… even if we know where our audience is coming from, we may feel that the underlying framework itself needs to be questioned.

For instance, I would take the refugee example a step further. The argument couched in patriotism is much improved, but it doesn’t get at the core issue unless it addresses the need to truly care for those who are different from us.

So, if the executive order (or any other hot topics) came up, I would craft an offer to move toward deeper compassion:

Remember how our grandparents came to the U.S.? You know all those stories about how they longed for freedom and opportunities, and how hard they worked when they got here? These refugees and immigrants are so much like them. And in our grandparents’ stories, they are never alone, trying to make it all by themselves. They talk about how people in their immigrant community and outside of it helped them. Now we can be those people outside of the immigrant community that help this generation of immigrants. We might even end up in their stories!

And here’s how this applies to business presentations.

We may think the decision we’re about to reveal to our team is obviously the best choice—it’s just self evident, right?

But how has our own moral framework guided our decision-making? We may think that the new project we want clients to buy into is the logical next step—it’s just common sense! Duh!

But is this project actually aligned with our client’s values as well as our own?

Without understanding what our audience most values, we may say things that contradict their values. Or we may say things that simply fall on deaf ears because they are outside of the person’s core values.

5. Understand their motivated reasoning.

If you’re facing an especially tough, “unpersuadable” audience, it’s tempting to say, “I respectfully disagree,” and launch into your arguments, points of view, mountains of data and proof, and even your most moving stories.

That’s what most people do and fail.

Sorry, but it’s true. Using mountains of data doesn’t work. In these cases, even storytelling doesn’t work.

That’s because none of this gets past people’s motivated reasoning. With motivated reasoning, people unconsciously start with the end in mind. They already know what they want to believe, and without even realizing it, they process information in a way that suits that goal. (See the work of Yale psychology professor Dan Kahan.)

Kahan cites a classic study where college sports fans were more likely to see referees’ controversial calls as fair if they were good for their team. Researchers concluded that students saw the tape differently based on “the emotional stake the students had in affirming their loyalty to their respective institutions.”

Our end goal can actually change what we see!

If a fact is personally threatening, people are less likely to believe it. For instance, people who receive news that they are ill are more likely to distrust the lab results than people whose tests show that they’re healthy. It’s possible to change their minds, but more information is required to prove them wrong.

Add social identity dynamics to the mix and changing minds gets even harder (as the college sports example shows). When a piece of information becomes an article of faith for a group, adopting a different opinion hurts your reputation within the group.

Think experts are easier to reach? Think again. Experts simply have “more tools to curate their own sense of reality,” says Matthew Hornsey, a professor of psychology at the University of Queensland.

6. Acknowledge their words.

One of the best practices for engaging your audience when they hold different beliefs or seem “unpersuadable” is to start by acknowledging their point of view.

Repeat what they tell you—verbatim— as much as you can. For instance, “So I hear you telling me that Mike slows projects down, so you don’t want him to be in charge of getting the focus group together.”

People aren’t ready to hear anything disagreeable until they feel heard.

Acknowledgement is like stabilizing ER patients before you perform life-saving operations. People aren’t ready to hear anything disagreeable until you’ve “stabilized” them by making them feel heard.

Don’t even think about shortcutting this process by saying, “I hear you, I know how you feel, I understand.”

No, you don’t.

Or at least, they won’t believe you until you repeat what they say verbatim.

Ask your audience to walk you through, on a mechanical level, how they came to their point of view. Most people are overconfident about how well they know how things work. But once asked to explain the mechanics, they realize that they actually know very little. So chances are good that your unpersuadable audiences don’t know as much as they think they do.

Get them to realize it gently, indirectly and respectfully. Now you have an opening to their mind and heart.

For example, a bank may currently process loans using paperwork and a manual process. But one of my clients wants to help them digitize the process. My client knows digitizing will require both a financial investment and a change in process. My client often hears the bank’s decision-makers say, “this costs too much.” However, the case my client makes is that in the long run, it saves you money. To make this argument even more effective, I encouraged the client to have the bank walk them through their cost analysis. By listening and having them go through it line by line, the decision-makers can see the gaps as well.

7. Aspire to a new story.

After acknowledging your “unpersuadable” audience, inspire them to envision a different future—one that’s more efficient, collaborative or compassionate.

And then encourage your audience to aspire to put that vision into practice. By acknowledging their current story (like in tip 6), you can lead them to embrace a new one.

By acknowledging their current story, you can lead them to embrace a new one.

Chapter Two: Crafting engaging stories

8. Tell universal stories.

To set the right tone with your audience, to establish trust and credibility, and to increase your persuasiveness, you have to come across as likeable.

Psychologist Robert Cialdini’s research on social influence shows that not only do we tend to like those we perceive as being like us, but we’re also more likely to form a stronger connection with them and find their ideas persuasive.

When a speaker begins a presentation with a story the audience can relate to, the audience perceives the speaker as “just like me.”

Immediately, a stronger connection begins to form.

To give a storytelling presentation that really connects, begin with a story that’s universal enough to make the audience think about how it harmonizes with their own story. Some universal (or near-universal) experiences might be:

- Having a great teacher

- Completing a physically challenging goal like a marathon

- Attending a school reunion

- Getting lost when traveling in a new city

I will often tell audiences the story of my experience taking statistics.

At first, I resented the fact that it was one of my required courses. Eventually, though, I came to appreciate how widely statistics could be applied. What changed? The stories this professor told. His stories convinced me that statistical tools were important.

I share this statistics class story with my audiences not only because it shows the difference stories can make, but also because most people in my audience will be able to relate. Chances are, we’ve all had at least one course we’ve resented being forced to take. But chances are also good that many audience members have ended up pleasantly surprised by one of the classes they most dreaded!

9. Tell leadership stories.

Leaders who want to connect with their audiences must go beyond simply telling a “good story.” Yes, a riveting story is the baseline, but stories told in business contexts also have to meet two other criteria:

-

Your audience has to know right away why you’re telling it.

-

They have to feel something and do something about it.

Start with these two criteria when you’re searching for the right leadership story. Consider the change you want to see and find the story that inspires emotions that will motivate people to act.

10. Choose a plot with the right emotional impact.

When it comes time to share these stories, another one of the best practices for engaging your audience is to structure your stories well. Do this using the five basic storylines that work best in business contexts.

Each of the storylines evokes a different kind of emotion:

- Origin stories inspire curiosity about a brand, organization or leader’s origins. A well-told origin story satisfies the audience’s desire to connect the dots between past and present in an inspiring way.

- Overcoming the monster stories provoke righteous indignation.

- Rags to riches stories promote empathy.

- Quest stories instill a sense of restlessness as the audience wishes for quests of their own.

- Rebirth stories evoke optimism. They’re all about second chances.

When you know what emotions each plot is likely to inspire, you don’t have to wonder, “How will my audience feel after my presentation?” You can guide and predict their emotions with greater accuracy.

For guidance, templates, and examples of how to construct three of these plots, see:

3 Basic Storylines You Should Be Using In Business Contexts.

Chapter Three: Gaining and Retaining Your Audience’s Attention

Hooking your audience’s attention and retaining it is a sign of respect. It acknowledges that their time and attention is a gift you don’t take lightly.

“The audience actually wants to work for their meal,” as Pixar screenwriter Andrew Stanton explains. “They just don’t want to know that they’re doing that.”

Stanton goes on to explain that because humans are natural problem-solvers, they pay attention when they find themselves needing to put two and two together. Hooking attention, then, is a matter of giving the listeners a problem to solve or a punchline to wait for.

11. Craft the initial hook.

Hooking your audience’s attention at the start of your presentation takes creativity. But that doesn’t mean you have to sit around waiting for the muse to arrive. You can jumpstart your creativity by trying one of these three methods:

1) Conflict.

A hook that uses conflict presents a clash of forces or needs going in opposite directions. It can even be a simple conflict. For instance, the mosquito’s need for blood conflicts with the vacationer’s need to be left in itch-free tranquility.

Kelly McGonigal’s “The Willpower Instinct” provides an example of a conflict-driven hook:

“The year was 1985, and the scene of the crime was a psychology laboratory at Trinity University, a small liberal arts school in San Antonio, Texas. Seventeen undergraduates were consumed with a thought they couldn’t control. They know it was wrong—they knew they shouldn’t be thinking about it. But was just so damn captivating. Every time they tried to think of something else, the thought bullied its way back into consciousness. They just couldn’t stop thinking about white bears.”

2) Contrast.

A hook that uses contrast juxtaposes opposite qualities like heavy and light, plentiful and meager or active and apathetic. For instance, you could describe the one quirky decoration in a leader’s otherwise nondescript office, emphasizing the juxtaposition of bland and eccentric.

The first paragraph of a recent New York Times article catches readers’ attention through a striking contrast: “It was designed by Bjarke Ingels, the renowned Danish architect, and cost $24 million to build. It was inaugurated by Queen Margrethe II, Denmark’s reigning monarch. And it now accommodates a celebrity couple with peculiar eating habits and an almost year-round animosity toward each other. Welcome to Copenhagen Zoo’s new panda house.”

3) Contradiction.

A hook that uses contradiction goes against your audience’s expectations. For instance, you could set up the familiar story of getting ready for a business trip, but then add the one detail that defies the usual narrative arc; for instance: “Did I mention that my 92-year-old grandmother was accompanying me?”

Robert Krulwich, co-host of WNYC’s RadioLab, uses the following contradiction to engage his audience: “When you unwrap it, break off a piece and stick it in your mouth, it doesn’t remind you of the pyramids, a suspension bridge or a skyscraper; but chocolate, says materials scientist Mark Miodownik, ‘is one of our greatest engineering creations.’”

Ask yourself this question now. After reading these openings, how do you feel? If you’re like thousands of people I’ve trained before, and one of your answers is “tell me more,” then you’ve experienced the full benefit of an effective hook. You want to know why chocolate has anything to do with the greatest engineering creations. Maybe you’ve already clicked on the link.

And this is what you want your audience to feel: that upon hearing the hook you laid out, they want to work out the ‘answers’ for themselves and hear whether their answers align with yours.

For more tips and insights on storytelling, sign up for Better Every Story, our guide to better storytelling.

12. Rethink your audience’s attention span.

Does your audience really have the attention span of a goldfish? Maybe not.

Attention is all about individuals and what interests them. “People can and do focus their attention well when they want to and are interested in a particular task or activity,” says Dr. Gemma Briggs, senior lecturer in psychology at The Open University. She notes that psychologists don’t consider “average attention span” to be a very meaningful concept.

This means there’s good news and bad news for speakers who want to catch their audience’s attention. The good news is that your audience’s attention span isn’t as short as others might have you think. You just have to be willing to work for it.

The bad news is that you do have to work for it. Are you willing? There is no magical formula here. Gaining and retaining your audience’s attention requires thinking differently. The status quo just doesn’t work.

Attention span is highly context based. Briggs says that how a person applies attention to different tasks depends on what that individual brings to the particular situation. What task are they trying to complete? What is their previous experience with similar tasks? What else are they trying to accomplish at the same time?

These are factors Briggs says can change audience’s attention levels. For instance, while listening to a keynote speaker, an audience member might be trying to grasp a concept that they hope will change their life. Likely they’ve attended other keynotes in the past–some that revolutionized their thinking, some that left them flat. While listening to the current keynote, they may also be trying to decide which session to attend next, wondering if they remembered to bring their hotel key or worrying about who they will eat dinner with. All of this factors into their ability to focus their attention.

13. Flip the script.

Briggs explains that we all have “cognitive rules of thumb, or scripts” for situations. She uses going to a restaurant as an example. “We have a script for what will happen: sit down, get a menu, order, get your meal” and so forth. “When we know what to expect,” says Briggs, “we may pay less attention as less cognitive effort is required.”

She theorizes that “if you put people in a situation which deviates from the norm for that particular task, and you ensure that they aren’t multitasking, you could in theory encourage people to apply more attention to the task.”

For example, what is your audience’s script for attending a presentation? A colleague of mine remembers showing up to an astronomy class where for the first few minutes, no professor showed up. Then, all of a sudden, someone in the third row started talking, raising questions about astronomy. It was the professor! He was sitting in the middle of the class, starting his lecture from his seat! The simple act of changing the script immediately caught the attention of a hundred undergraduates.

What is your audience’s script for attending a presentation?

Briggs stresses that each person will differ in what they bring to the situation and how much attention they apply–so flipping the script may be effective for some and not others.

14. Play with words.

Imagine you’re sitting in the audience, listening to a long lecture. If it’s still holding your attention, chances are you’re thinking along with the speaker, trying to anticipate what she’ll say next. As Roger Dooley points out, there’s research showing that our brain tries to predict the words that come next, much like the predictive text suggested by our phones or search engines.

For engaged audience members, it’s rewarding when a sentence takes even a tiny unexpected turn. When you expected the speaker to say “it’s all about following the manual,” but instead the speaker says “it’s all about following the manicure,” your ears perk up. You want to know what manicures have to do with the topic at hand!

Similarly, we listen up when we hear one part of speech being turned into another.

Remember the first time you heard the now-ubiquitous “adulting”? It caught on not only because the concept resonates with many people, but also because, as Dooley mentions, hearing someone turn one part of speech into another increases our brain activity.

Audiences love wordplay.

15. Make clarity the goal.

“Many speakers think that the goal is to prove that the speaker knows their stuff,” says Dr. Steven M. Smith, professor in the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences at Texas A&M, “but the real goal is to get a clear message across. Audiences remember only a few things from any talk, so the speaker needs to know exactly what those few things are, and present them with as little distraction as possible.”

What are some possibly counterproductive distractions?

It boils down to irrelevant information.

Smith cites “having too many words on the screen, having cute but irrelevant things on the screen and funny but irrelevant jokes.”

16. Repeat yourself.

Find ways to repeat key terms in a non-patronizing way.

“Telling people something only one time,” says Smith, “especially the meaning of an important term or an acronym, does not mean that the audience will remember it for the rest of the presentation. If someone misses the original explanation, or forgets it 30 seconds later, they can be totally lost. Use frequent reminders!”

Repeat key points.

Define key terms more than once.

17. Check for understanding.

Has your audience really heard your message?

Yes?

You’re sure?

Well, there’s a difference between hearing and understanding. So find out if they have understood or were just smiling and nodding.

“Check in now and then with the audience,” Smith advises. “Ask a question, ask for a show of hands, to see if they get what you said. A risky, but potentially effective strategy is to make a relevant joke that can be understood only if the audience gets the point– no laughs shows that they didn’t get it (or that you aren’t as funny as you thought you were).”

Read the full interview transcripts with Dr. Gemma Briggs and Dr. Steven M. Smith here.

18. Understand the “flow state.”

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the first psychologist to study flow state, describes it as being so totally engrossed in the task at hand that we feel our “existence is temporarily suspended.”

It’s the state of mind that makes video gamers lose track of time. It’s what many people feel while competing in a favorite sport, playing an instrument, designing a new product, reading a good book or doing other challenging things that they love.

So how do you create that flow state?

Let’s turn for a moment to the world of video games. Video gamers regularly find themselves in a flow state, seeing dawn approaching when they could have sworn it was still 2 p.m.

19. Create a world the audience sees as “real.”

“Well, duh,” you might be thinking. My story really did happen. And maybe it even happened in a setting that’s completely familiar to your audience: a break room, an office, or the deli your department tends to flock to.

That’s helpful. Video gamers find that when environments come from settings they’ve seen depicted before—say, the wild West or a World War II battlefield— they can fill in the blanks “without being pulled out of the world to think about it,” as psychologist and video game consultant Jamie Madigan puts it.

Even when the environment is familiar, game designers recommend including “multiple channels of sensory information” to make players feel like they’re immersed in that imagined world.

It’s the same with business storytelling.

You don’t have to give pages of flowery description. But does the break room smell like coffee? Can you hear the hum of the vending machine? If so, we’ve just stepped into your world.

20. Keep them in that world.

Now that your audience has stepped into your world, don’t let anything jar them out of it.

For video games, says Jamie Madigan, this is “anything that reminds you that ‘Yo, this is A VIDEO GAME.’”

For business presentations, mentioning the budget will wake the audience up to the fact that “oh, yes, this is a business presentation.”

Likewise, mentioning a timeline—especially when the deliverable is due earlier than the team expects—will jolt everyone back to reality.

When you need to mention budget and timeline (as, inevitably, you will), know that you will be issuing a wakeup call that is going to interrupt the flow state.

Save these wakeup calls for the end, as you move from story to action plan.

21. Make them work.

Think about the last video game you played. Even if it was a while ago and you have to dust off your memories of The Legend of Zelda or Tetris, you probably remember what happened when you were playing the game and a friend asked you a question.

The “GAME OVER” screen flashed before your eyes before you even thought of your reply. This need for intense focus is what creates the flow state.

In a video game, you’re working to keep up with what’s happening on screen. You’re working to figure out how to stay alive, how to beat this level and move to the next.

Likewise, you want your audience to be working with you to think about how the story is going to develop.

With a story, the challenge is not to stay alive or make it to the next level but to think alongside the storyteller and anticipate how the conflict will resolve.

22. Keep them guessing.

“Part of what makes games addictive,” writes N.L. in The Economist, is “requiring an unpredictable number of actions in order to earn a reward. Giving one at regular intervals means that a player, having received a reward, will be less motivated to play on.”

As always, the best practice is to spend some time analyzing your audience.

What do they need?

Why have they signed up for your session or been invited (or forced) to attend this meeting?

What do they want to know?

Intrigue your audience from the get-go. Then give them the information or resolution they seek just a little bit at a time.

Give them crumbs.

Curiosity really is that powerful. A recent study showed that some university students would take the stairs instead of the elevator if they saw a trivia question posted by the elevator along with a promise that the answer was in the stairwell.

“People really have a need for closure when something has piqued their curiosity,” says study co-author Evan Polman, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “They want the information that fills the curiosity gap, and they will go to great lengths to get it.”

23. Use visuals to hook curiosity.

Roger Dooley, author of Brainfluence, points out that we experience a neurochemical reward whenever we acquire new information. The new material doesn’t have to be profound. Even a new, unfamiliar photo can keep an audience’s attention.

When someone trots up to the whiteboard or grabs a napkin and starts drawing, immediately, we want to learn: “What are they going to draw?”

Everyone watches.

As Steve Franconeri, a cognitive psychologist at Northwestern University puts it: “If you get your visual on the whiteboard, it dominates the meeting.” It can be the most primitive illustration, but it captures your audience’s attention because their brains are working.

As the audience focuses on the drawing, watching it develop, they are thereby engaging with what you have to communicate.

Satisfying your audience’s curiosity is one of the best rewards you can offer whenever you need to give a presentation.

Chapter Four: Beyond presentations, beyond your comfort zone

1) Best Practices for engaging your audience through email

How do you intrigue your email audience right from the moment your email lands in their inbox?

Three tips (bringing us to tips #24-26).

24. Make your subject line specific.

Indicate what the goal or ask might be. Some examples:

- “Article on [recipient’s area of expertise] for Forbes”:

A member of my team crafted this subject line in order to connect me with a subject matter expert to interview for a recent Forbes article. The subject matter expert replied 13 minutes after the email was sent! Why? Maybe it caught him right as he was sitting at his desk and he likes to respond quickly. But maybe he recognized, just from the subject line, that this request presented him with an opportunity to have his name and insights appear in Forbes, and he wanted to jump on that opportunity.

- “How to Implement Meaningful Change on Your Campus”:

This email marketing campaign was an invitation for readers of The Chronicle of Higher Education to read an in-depth report–but instead of starting with “hey, read our report!” they led with what the readers would get out of it. Very effective!

- “[Name of organization] fundraiser help needed”:

This includes the specific ask, and it is from a nonprofit that one of the Leadership Story Lab team members volunteers with on a weekly basis.

Unfortunately, the subject line included an acronym of the nonprofit’s name, rather than the full name, so the recipient didn’t realize what it was about! (It’s an acronym very few volunteers use for the organization.) She almost marked it as spam! Once she realized what the acronym stood for, she was eager to help and opened the email right away.

Takeaway: know your audience! What name do they know you by? What will gain their trust?

- “All Hands on Deck for the Next Sales Deck”:

This is the subject line that kicked off a project for a client’s sales deck used by its team of around 450 people. It signals the urgency, importance and has a small word play.

- “Chicago Connection” or “Reena, meet Darin”:

Our COO, Reena, says that subject lines with “meet” or “connection” always catch her attention. With subject lines like this, there’s no guesswork about what it’s about–and an invitation to network is often intriguing.

25. Keep it mysterious.

Make it not quite clear what the email is about. Some examples:

- “We prefer ‘To Be Continued’ over ‘The End.’”

Our friends at the meetings and special events venue Catalyst Ranch are pros at creating subject lines that inspire curiosity. Can you guess what this email is about? It’s about how they re-purpose objects like vintage wardrobes in order to spark attendees’ curiosity. So that object’s life is “to be continued” rather than ending in a landfill! That’s not what one would guess from the subject line, and that’s a good thing! Customers will be impressed with their creativity and eager to book their events there.

- “Can big data kill creativity?”

Framing this as a question keeps just enough mystery so that the recipient wanted to open the email and see what it was all about. This was, it turned out, an invitation to comment on a LinkedIn post. But instead of starting with, “Can you please comment on my LinkedIn post?” the sender started with the topic of the LinkedIn post.

An intriguing, riveting and satisfying email takes time to craft. If no one opens the email, all that effort is wasted! So the extra time spent crafting an attention-getting subject line is well worth it.

Now, for the content of the email, the same general storytelling principles apply.

My best advice is….

26. Structure is everything.

Get your email’s recipient(s) to pay attention to your important content by using the storytelling technique of “IRS.” (You can also use this structure for anything that needs to be short and sweet (whether an email, tweet or elevator pitch).

Just remember:

- Intriguing beginning

- Riveting middle

- Satisfying ending

Here’s how Priyanka Murthy, a friend of ours, was able to use the IRS structure in an important email.

Case study: Priyanka Murthy Of Access79 Jewelry

As she started a new company, Access79, Priyanka Murthy found herself needing to write many emails to complete strangers. Access79 is a “try-before-you-buy” luxury jewelry service; Murthy describes it as “the Stitch Fix of fine jewelry.”

To start the company, Murthy needed jewelry designers. So she reached out to them via email. She knew storytelling would be essential to persuading designers she had no existing relationship with. It’s true that people make decisions based on facts, she says, but they also decide based on their gut, and stories address that. Stories are part of what Murthy calls people’s “decision-making metric.” Here’s how she made the most of a short email to the designers she wanted to work with.

Intriguing Beginning:

- In the first line, she intrigued her audience by establishing what she calls “authentic relatability.” So she introduced herself as a fellow designer. She had, after all, been the sole designer when she started another company, Arya Esha Designer Jewelry, in 2015. After building this rapport with her audience, she added a line letting them know how she knew of this designer and why she wanted to work with them. The emails were especially powerful, Murthy notes, if she could say, “a client told me about you.”

Riveting Middle:

- After this intriguing opening, she’d explain her business model using only one line, so that she could quickly move on to a story about why Access79 was important. What was the pain point for the customer? What was she trying to solve? She would tell a story about a customer who messaged Murthy’s company Arya Esha to say that because she had two sets of twins, in-person fine jewelry shopping was not a viable option, so she was not able to visit any of the stores where Arya Esha jewelry was sold. However, she did not fully trust buying online either. She wanted to be able to try the jewelry on.

Satisfying Ending:

- Murthy then ended with the line, “We’re launching Access79 to solve this problem.” She then asked them if they would be willing to meet with her face-to-face.Did every designer respond to her emails? No. But for those who did respond, it was because the story resonated. They had similar experiences with customers expressing the same pain point! When the story resonated, the designers did want to meet Murthy in person and continue the conversation.

As Murthy found, storytelling doesn’t have to be about a long epic battle. In the modern age, you can apply the “IRS” format to everything that involves communication.

2) Best practices for engaging your audience during one-on-one conversations

Have you ever watched kids build forts, castles or cabins out of simple materials? All they need is a pile of plastic poles and a few handfuls of connector pieces. With these tools in front of them, the output is only limited by their imagination.

This simple combination is a good metaphor for persuasion. You have piles of stories. After all, you’re sitting on a goldmine called “life.”

And since the person you’re trying to persuade is also sitting on a goldmine of their own, they also have an abundance of stories.

Persuasion is what allows you to connect your story with theirs.

It’s like the connector pieces kids use for their imaginative building projects. Without the connector pieces, there is no structure and no bonding agent.

But if you can find that magical mechanism that locks your story together with other people’s, you can begin to persuade them–whether they are a hiring manager, prospective client, employee, colleague or anyone else you want to join your cause.

Finding that “lock” that authentically intersects your story with someone else’s is what makes persuasion happen.

Persuasive stories enable you to establish rapport, build relationships, and earn trust from your audience so that they see you as truly in the same tribe.

Here are my tips for finding connection.

27. Mine their stories.

The first step is always to consider your audience’s stories. Invest time in getting to know the person you are talking with.

Listening to the audience’s stories made the difference for my client Margaret Page when she was campaigning to be the 2nd Vice President of Toastmasters, a position that could set her on the path to become the organization’s president.

She called 500 Toastmasters members from all around the world and had one-on-one conversations with them. She heard their stories of how Toastmasters had made a difference for them.

Her listening paid off: Page won the campaign and is now on the path to climb to the top of a renowned international organization.

Download our Crazy Good Questions to inspire reflection and storytelling in conversations.

28. Find the concept behind the story.

During the conversation, pay attention to the specific events, time periods, plots and characters that your audience communicates in their stories. Based on these, what ideas are important to them?

For example, when someone is struggling with whether to join the family business or strike out on her own, she could really be trying to find her professional identity.

When someone is trying to fend off a market threat from a major competitor, he could actually be struggling to innovate within his company.

Find the high-level concept behind each story you mine.

29. Choose an intersecting story from your own “Story Library.”

Consider the stories from your own life. Which ones will best resonate with the concept the person is talking about?

It does not have to be an identical story.

For instance, if their story has an underlying of searching for professional identity, tell a thoughtful story about a time when you struggled to find your own professional identity.

30. Time it right.

Timing is everything. When should you introduce your story?

You don’t want to come across as trying to tell a better story than the one just told. Nor do you want to shift the focus to yourself.

And if someone happens to share a sensitive story–an experience of discrimination, trauma or grief–don’t search for an intersecting story at all. Simply listen well and affirm what they are sharing.

When the situation is appropriate for sharing a story of your own, however, there are three phases for telling an intersecting story:

First, fully acknowledge that you’ve heard their stories and that you empathize.

Second, share stories that intersect with theirs on a conceptual level. It doesn’t have to be immediately following their story.

Third, together, imagine a future story that captures yours and theirs. You could preface this with a phrase like, “What would it look like to…?” or “Based on our shared interests, what if we….?”

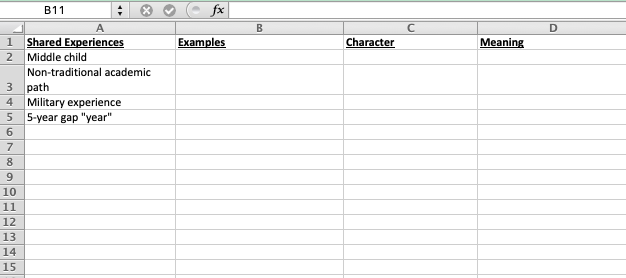

31. Keep building your story library.

In order to find intersecting stories, one of the best practices for engaging your audience is to fill your own “story library” with good stories.

Reflect on your own life experiences and shape them into brief stories that you feel prepared to tell at a moment’s notice.

Get organized!

Consider the experiences you’ve had that somebody else is likely to share. Develop the example, and reflect on what it says about your character and what meaning it holds for you.

Another way to generate stories is to download our Crazy Good Questions and use them to reflect on your own experience.

When you find intersecting stories, you can begin to build countless good things with the people you’ve authentically persuaded to join you.

3) Best practices for engaging your audience when you’re an introvert

stage spotlight

I firmly believe introverted business leaders can tell some of the most compelling stories, that they should tell their stories because of all we know about how persuasive stories are, and that they will most likely find it incredibly fulfilling once they do.

So here are my best tips for telling stories if you’re an introvert:

32. Keep track.

Be on the lookout for stories in everyday life.

Keep track of them, and reflect on what they mean.

33. Prepare.

Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking recommends practicing your story or presentation “out loud until you’re comfortable. If it’s an important speech, videotape yourself. The main reason public speaking can be uncomfortable is that you have no idea how you’re coming across.”

Practice and videotaping can remove this uncertainty. Cain also recommends watching lecture videos where you can see the speaker’s view of the audience. This lets you pretend you are the speaker.

34. Make it about them.

Worrying over how your performance will go and nitpicking every detail afterward are good ways to kill the joy of sharing stories!

Instead, shift your attention to what your audience needs (see Chapter One, above).

35. Slow down.

Talk slowly, and try to slow down the pace of your thoughts as well, says public speaker Tyler Tervooren.

When our brains get ahead of our words, we stumble. We forget where we are. So, “when you notice your brain skipping too far ahead, you just tell it to go back and repeat itself. Wherever your mouth is, that’s where it needs to jump back to, and start over again.”

So step up to the microphone, confident to share the stories you have prepared. And prepare to be amazed at the connections you will make.

Fundraisers: Taking the time to understand donors’ character allows you to lead with the right messaging—to lead with stories that will resonate and build a stronger partnership. Explore Leadership Story Lab’s research on understanding first-generation wealth creators, an often misunderstood subset of major donors.

Photo credit for first photo of Esther Choy in this article: Eddie Quinones.

Better Every Story

Leadership Transformation through Storytelling

"This is an amazing and insightful post! I hadn’t thought of that so you broadened my perspective. I always appreciate your insight!" - Dan B.

Get Esther Choy’s insights, best practices and examples of great storytelling to your inbox each month.