Aligning the key values of first generation wealth creators and fundraisers in the age of “Winner Takes All”

“A new report by the Leadership Story Lab… looks at three areas where small changes by gift officers could reap large benefits for their nonprofit organizations.”

- Paul Sullivan, The New York Times

Our new report, Transforming Partnerships With Major Donors, was featured in the Wealth Matters column in the New York Times. Read the report below!

Our new research report explores the misunderstood stories of first-generation wealth creators, with an eye toward helping fundraising executives strengthen their partnerships with this major subset of donors who are equipped to make transformative gifts.

“As a donor, I’m thrilled to read research that focuses on wealth and its impact on donors as people, parents, friends, and members of an extended family. This research will help fundraisers understand that wealth is a new phenomenon for the majority of the wealthy people in this country.”

-Jennifer Risher, author of We Need To Talk: A Memoir About Wealth, and co-founder of #HalfMyDAF

An Honest Conversation About Wealth and Philanthropy

Change can only happen when we take the time to listen and learn from each other. In this webinar, we started doing just that. Hear from our panelists, Lisa Greer, Scott Mordell, and Jennifer Risher, as they share personal stories and experiences around wealth and philanthropy.

“The report makes the case well that fundraisers and nonprofits simply can’t afford to keep legacy methods in place that make FGW donors uncomfortable. With (over) 60% of donors being in this category, and the sheer amount of wealth at stake, it’s an imperative that these organizations embrace and acclimate to the obvious change in their ‘target audience.’”

-Lisa Greer, author of Philanthropy Revolution: How to

Inspire Donors, Build Relationships and Make a Difference

"Transforming Partnerships with Major Donors" Enhanced Report

In this report:

- Executive Summary

- Unexplored Wealth & Misunderstood People

- Who are they, really? Key values of first-generation wealthy

- What to do? Never more of the same

Executive Summary

To secure a major gift, naturally fundraising executives must find wealthy donors. But what if a huge swath of donors who are in a position to give transformational gifts do not consider themselves “wealthy” at all?

A full 68% of wealth is currently earned rather than inherited. And these first-generation wealth (FGW) creators feel that the “wealthy” label represents a set of values they simply don’t adhere to, as Leadership Story Lab found in lengthy interviews with twenty first-generation wealth (FGW) creators. Foremost among their values is the concept of “stealth wealth”—they avoid showing off their wealth and maintain their native middle-class values.

Still, FGWs crave meaningful ways to allocate their vast financial assets; thus, they seek transformative partnerships with nonprofits. However, many feel alienated from the surrounding philanthropic circles. Splashy events feel antithetical to many in this subgroup, who say that just as they strive to be modest in spending and appearance, so too do they avoid charitable events and organizations that feel like an “in-club” for the very wealthy.

Fundraisers must recalibrate or risk losing millions. The fact is, even as the amount of wealth in the United States is expanding, the number of people who control that wealth is shrinking. Because the majority of wealth is currently earned rather than inherited, most major donors will fall into this misunderstood category. Although fundraisers are competing for a growing pool of assets, a smaller number of decision-makers will allocate those funds. In short, fundraising is becoming a “winner takes all” proposition.

Fundraisers must recalibrate or risk losing millions. The fact is, even as the amount of wealth in the United States is expanding, the number of people who control that wealth is shrinking. Because the majority of wealth is currently earned rather than inherited, most major donors will fall into this misunderstood category. Although fundraisers are competing for a growing pool of assets, a smaller number of decision-makers will allocate those funds. In short, fundraising is becoming a “winner takes all” proposition.

Despite numerous research studies illuminating the unique life journey of FGWs, few major gifts officers are aware of their existence, and thus, undermine their ability to connect and appeal to these game-changing donors. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Fundraising leaders and executives can bridge this gap, demonstrating that they understand the FGW mindset, and that their organizations are part of their tribe. Leadership Story Lab’s research furthers the conversation about key attributes of this subset of wealthy donors and aims to close the gap between the existing knowledge and those who can use it.

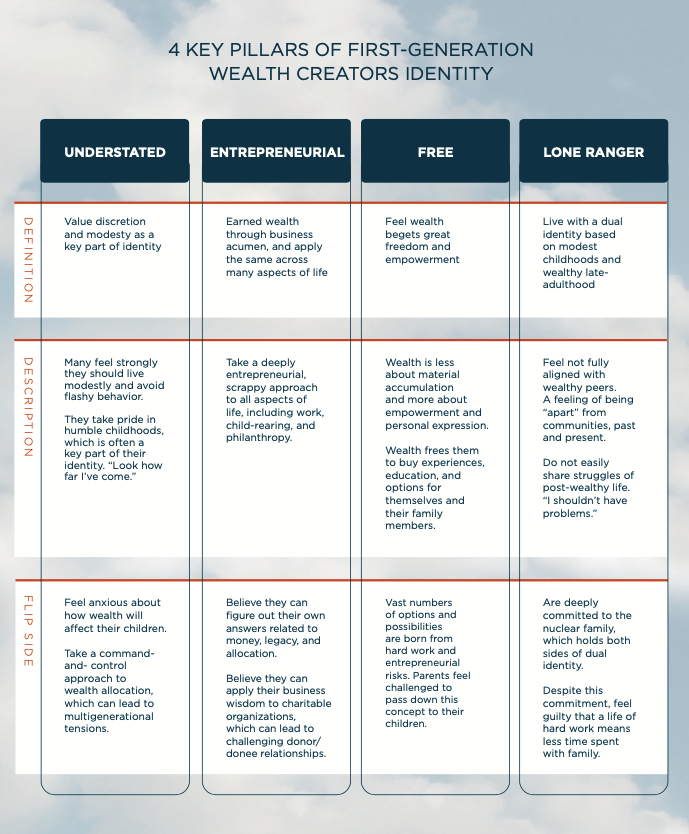

In this research report, we explore deeply held values of first-generation wealth creators in order to understand how these values can rejuvenate partnerships between major donors and fundraising executives. Modesty was one vital attribute, while others include:

- An entrepreneurial approach to life (and to partnering with philanthropic causes).

- A prudent exercising of their freedom and wealth of options and influence.

- A desire to raise responsible, self-motivated children and grandchildren (a wish that becomes a source of profound worry for many).

How can philanthropic institutions show that they understand this group and are part of this tribe of unique and rarely understood donors? Our report’s conclusions point the way toward key ideas to spark change--helping fundraising executives attract transformative gifts that sustain mission and fuel long-term planning.

What follows is an abridged version of the report that has been enhanced with further Leadership Story Lab resources, including selections from Esther's book Let the Story Do the Work. Read on, or download the full report as a PDF.

Questions or thoughts? We'd love to hear from you any time.

Unexplored Wealth & Misunderstood People

First-generation wealth creators have profoundly different life experiences than multigenerational wealthy individuals. Those differences — and the values they beget — should be top-of-mind for fundraisers.

Contrary to popular belief, most wealth in the United States is not passed down but earned. Of the ultra-wealthy (those with $30m or more in assets), a recent Wealth-X report says that 68% wholly created their own wealth, 24% say their wealth is made up of inherited and self-made monies, and just 8% say they fully inherited their wealth.

Contrary to popular belief, most wealth in the United States is not passed down but earned. Of the ultra-wealthy (those with $30m or more in assets), a recent Wealth-X report says that 68% wholly created their own wealth, 24% say their wealth is made up of inherited and self-made monies, and just 8% say they fully inherited their wealth.

Despite numerous research studies illuminating the unique life journey of FGWs, few major gifts fundraisers are aware of their existence.

The lack of understanding about this specific group of wealthy people is a critical stumbling block for fundraising executives and their major gifts officers, who must build relationships with individuals and families of means but may struggle to identify them and relate to them, or may lead the conversation with the wrong messaging.

Taking the time to understand donors’ character allows fundraisers to lead with the right messaging—to lead with stories that will resonate and build a stronger partnership.

This new study by Leadership Story Lab refreshes the conversation and closes the gap between the existing research and those who can use it most.

In our research, we share insights about the struggles and values of first-generation wealthy individuals and families in 2020 — all with an eye toward informing the fundraising executives who outreach to them.

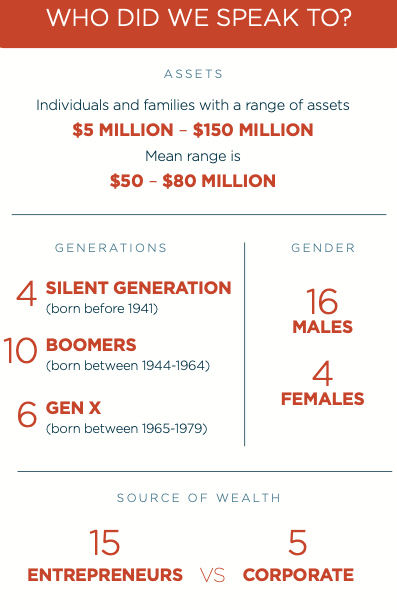

Our report is based on lengthy interviews with 20 first-generation wealth (FGW) creators and families, all of whom live in the United States. We defined a FGW creator as someone with at least US$5 million in assets. The median net worth in our set of 20, however, ranges between $50 million and $80 million in assets. The interviews were undertaken by Mantis Research, and all interviewees were granted full anonymity.

Learn more about unexplored wealth in the full report. Download the PDF below.

Stay current with our research and storytelling insights by receiving Better Every Story.

Who are they, really? Key values of first-generation wealthy

Those who built wealth in their lifetimes feel deeply confident about their business acumen and the personal values that propelled them to success. Yet this confidence can lead to tensions: within families, with philanthropic institutions, and with wealth advisors.

The majority of individuals we spoke to admitted they fit our definition of wealthy but don’t identify that way. Many felt discomfort with the word “wealthy,” saying it represents a way of living and a set of values they don’t adhere to.

One person explains, “We don’t consider ourselves wealthy. We’ve been able to accumulate more than we ever dreamed, no doubt. But living among a group where there’s lots of trust fund babies … they have never worked a day in their lives.”

Another shared, “I don’t know if I’m wealthy so much as I’ve become rich. … Wealth has a size to it in this day and age and a bit of longevity to it.”

This accords with James Grubman’s findings in his 2013 book Strangers in Paradise, in which he envisions the newly wealthy as “Immigrants to the Land of Wealth.” They journey to this new land, yet often feel estranged from it.

We wanted to understand: How do their modest upbringings influence them today, and what do they perceive is different about their own values and self-identity, compared to their high-net-worth peers who grew up wealthy? And how can understanding their identity transform relationships between first generation wealth creators and major gift executives?

UNDERSTATED in every way

First-generation wealthy we spoke to feel strongly that moderation and modesty is a family value, even while they may make purchases that are in keeping with their current socioeconomic level (e.g. multiple homes, vacations, private schools, etc.). One explained, “I’m very self-conscious about [our wealth]. I don’t want to flaunt it.”

First-generation wealthy we spoke to feel strongly that moderation and modesty is a family value, even while they may make purchases that are in keeping with their current socioeconomic level (e.g. multiple homes, vacations, private schools, etc.). One explained, “I’m very self-conscious about [our wealth]. I don’t want to flaunt it.”

Because this group identifies strongly with their modest childhoods, they speak with pride of the lessons they learned about hard work and persistence, born from deprivation. “Wanting for some material things has a positive side to it. It makes you think about why you’re here on earth and how other people are dealing with crises,” explained a retired business owner.

Another entrepreneur who now runs a family foundation part-time reported, “When my Dad was laid off for a long period of time, we ate a lot of bologna sandwich dinners, just trying to survive. They were really struggling. ... I see other people who live in a bubble. They don’t understand what it’s like. Once we came into money, I took it very seriously to make sure we would never be without it again. And to take care of certain members of my family.”

This emphasis on modesty can run counter to some of the advisory services that outreach to them, though there has been an emerging trend to change this.

One interviewee explained, “The old model of addressing high-net-worth individuals with very slick settings … with highly trained people with educational pedigree and so forth. ... There’s a clientele that appeals to; it’s sort of viewed as a badge of honor: I’m wealthy enough to be in so-and-so’s private banking group. A lot of those institutions are still trying to operate under that model. I don’t think that works with the [younger FGW].” That individual is just about getting solutions and not the packaging.

Our report also found that FGWs' strong entrepreneurial drive contributes strengths – and tensions – as they partner with nonprofits.

FREE to be who they are and choose how to contribute

Many first-generation wealth creators say the benefit of great wealth is not the ability to purchase things, but rather the wealth of options and freedom it begets. One interviewee shared, “Wealth allows you to become — at least, in my case — self-sufficient and able to cope with problems as they come up.” Another shared a similar sentiment: “Money doesn’t buy you happiness, but it does buy you options.” Yet another shared, “Well, I think the most important [benefit] is knowing that you have a freedom of choice.”

Many first-generation wealth creators say the benefit of great wealth is not the ability to purchase things, but rather the wealth of options and freedom it begets. One interviewee shared, “Wealth allows you to become — at least, in my case — self-sufficient and able to cope with problems as they come up.” Another shared a similar sentiment: “Money doesn’t buy you happiness, but it does buy you options.” Yet another shared, “Well, I think the most important [benefit] is knowing that you have a freedom of choice.”

For one individual, “options” include the ability to teach his children by visiting interesting cities and learning from other cultures. Another agreed, “It’s about the opportunity to learn and be exposed to different cultures. … I think about, What if I had that [chance when I was young]?’” In this way, wealth helps families express their values, not through acquisition but through travel and education.

“Wealth as possibility” extends also to the way this group views their charitable donations.

Interviewees shared that they choose nonprofits that allow their donations to promote the kind of empowerment that helped them in childhood. One shared his ethos for charitable giving, saying philanthropy for him was about giving young people and families the options he was denied as a child; specifically, he aims to “take education and economic opportunities, and pair them for empowerment of individuals and families.”

Wealth also begets tremendous influence. One interviewee explained that for her, wealth is not about affording things, but about making positive changes in her community. She explains, “what's becoming increasingly interesting to me is how many times, because I have a successful business, people ask my opinion. Today I’m going to the governor's economic recovery task force to help them with [redacted]. You get the opportunity to provide input and to manage things on a larger, higher level. That is so valuable. You can only buy so many damn things.”

FGWs often feel alone as they navigate wealth and philanthropy.

They also worry that inherited wealth will ruin their children's lives. How can fundraising executives show understanding and empathy? How can they open doors for donors to share their values with the next generation? Our report shares more.

Build meaningful relationships: learn the tools in our business storytelling training.

What to do? Never more of the same

First-generation wealth creators hold the key to a large proportion of transformative gifts. Yet, they feel apart from the charitable social events and institutions that cater to wealthy families. How can philanthropy professionals bridge this divide?

For major gift executives, a big challenge is a phenomenon called “stealth wealth” by Jim Taylor, Doug Harrison, and Stephen Kraus in The New Elite. Given their more modest backgrounds, first-generation wealthy still identify with middle class values even if their assets place them squarely in the top 1%. In that study, 89% agreed, “I believe in ‘stealth wealth’ — having money but keeping it under the radar.” In our interviews, individuals strongly agreed, saying they are never transparent about their personal assets when speaking with fundraisers or gift advisors.

Another shares, “I haven’t found anyone who, in my mind, has really cracked the code on how to deal with first-generation wealthy. Everyone seems to be chasing it the same way as what they’ve been doing.”

Roughly half of the first-generation wealthy we spoke to feel put off by the philanthropic social circles that surround them.

Some first-generation wealth creators “think you should always give anonymously,” James Grubman, author of Strangers in Paradise, told Leadership Story Lab in an interview. “Because otherwise you are being… egotistical, which is what they thought of Rich People who put their names on college buildings. They don’t understand the value of inspiring others to give by being visible in your own giving.”

Splashy events feel antithetical to many in this subgroup, who say that just as they strive to be modest in spending and appearance, so too do they avoid charitable events and organizations that feel like an “in-club” for the very wealthy. This is particularly true for those below the age of 55, who no longer wear a shirt and tie to work, and are loath to wear them for any event aside from a wedding or funeral.

The mismatch of event styles and spending decisions by nonprofits is a signal to FGWs that the organizations actually do not understand their donors’ values, that they are not really a part of their tribe. Tightly intertwined with this misalignment of values is the direct implication of wasting money, and therefore, wasting time.

One of our interviewees put it this way, “We gave a lot of money to [name redacted]. I organized two or three events. We spent not just money, but a lot of time organizing events. This was 10 years ago, when they were first becoming a bigger organization. I met with two or three of the organizers that I thought were good people. Then you read about how much money was frittered away on the administrative side of that organization. You sit there and watch these TV ads day in, day out. Those things are costing a fortune.”

Showing that you are part of a donor’s tribe starts with thinking deeply about what you already know about them. However, it is just as important to identify what you don’t know. Identifying and fixing your blind spots gives you a panoramic vision of your donors.

This simple exercise guides you to take inventory of the knowns and unknowns.

In light of all of our research, how can philanthropic institutions attract transformative gifts that sustain mission and fuel long-term planning? The full report outlines four key ideas that warrant further discussion.

Download The Full Report

Be one of the first to read the new report, “Transforming Partnerships with Major Donors.”

Please share your information to download the research report.

FGWC Research Publish Notification

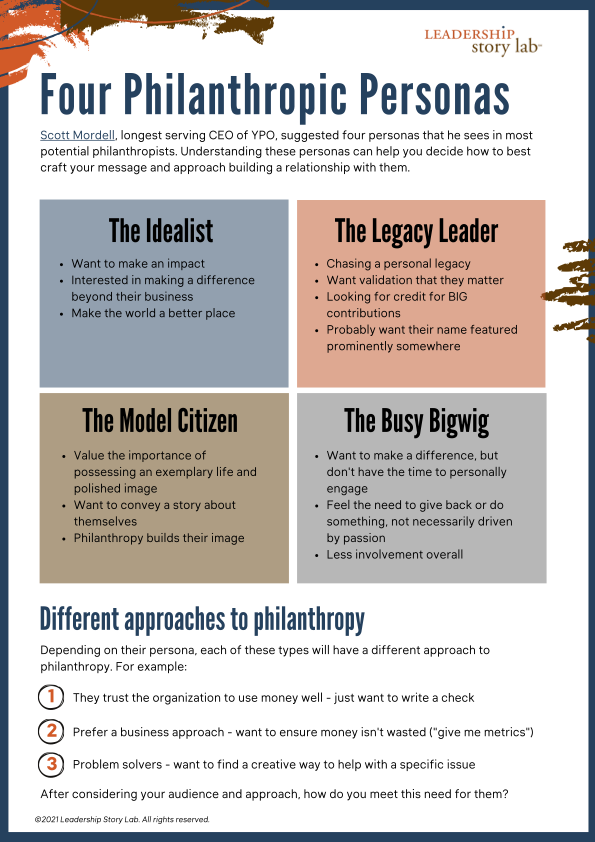

Download the Four Philanthropic Personas Handout

Scott Mordell, longest serving CEO of YPO, suggested four personas that he sees in most potential philanthropists. Understanding these personas can help you decide how to best craft your message and approach building a relationship with them. This companion handout contains frameworks to prepare you for conversations with donors.

Fundraising executives: First-generation wealth creators want to partner with you, but many won’t. So many current philanthropic practices were based on customs set nearly two centuries ago. They’re out of step with the current needs and interests of this elite group of donors today. If you’d like to start a conversation on how to get your team to be better equipped and your strategy more donor-centric, drop us a note.

First-generation wealth creators: Our research has revealed that even though each FGW is unique, many share surprising commonalities and can benefit from learning more about the experience of others in their new tribe. We invite you to contribute your stories and experiences to this ongoing research, while learning from the insights of others who are contributing alongside you. Please contact us.

Business Storytelling Insights

Better Every Story

Leadership Transformation through Storytelling

"This is an amazing and insightful post! I hadn’t thought of that so you broadened my perspective. I always appreciate your insight!" - Dan B.

Get Esther Choy’s insights, best practices and examples of great storytelling to your inbox each month.

Listen to Esther's Podcast: Family IN Business

Nearly every single FGW we interviewed described anxiety and regret about the experiences of their children growing up with wealth, compared to their own experiences. That’s why we think first-generation wealth creators will find support and inspiration in Esther’s podcast with Kellogg School of Business, “Family IN Business.”